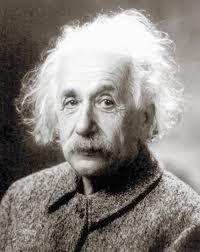

said the famous Albert Einstein. Even before him the first translator of Buddhist Pali texts into German, the most talented Karl Eugen Neumann, one of Europe’s first practicing Buddhists, noted in one of his prefaces to the Middle Length Sayings that Buddhism, though originating from 600 before Christ appears rather as a religion from 600 years after Schopenhauer, i.e. 2460 CE ;-)[2]

It was the reading of Schopenhauer which threw the young Neumann out of his normal worldly life and made him abandon his well paid job as a banker. He went back to university studying Sanskrit and Pali day and night for the next years to get as close to the words of the Buddha as possible. He dedicate the rest of his life to the translation of those words of wisdom.

It was the reading of Schopenhauer which threw the young Neumann out of his normal worldly life and made him abandon his well paid job as a banker. He went back to university studying Sanskrit and Pali day and night for the next years to get as close to the words of the Buddha as possible. He dedicate the rest of his life to the translation of those words of wisdom.

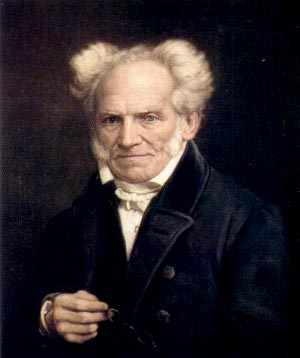

Just how incredibly close Arthur Schopenhauer, who assimilated a long standing tradition of Western philosophy[3], from Plato, Spinoza to Kant, came to the range of ideas as expressed in the early Buddhist suttas will be more than obvious and quite astonishing to anyone who cross reads his “World as Will and Presentation” with the early suttas. For a Buddhist convinced in rebirth, this “co-incidence” is not of such great a marvel, however 🙂

Below an entirely random number of quotes from just a handful of passages I was reminded of, reading in the new excellent English translation of Schopenhauers work. Please read Schopenhauer’s idea carefully and then compare it to the Pali passages which I matched accordingly.

If you are well embedded in Western culture and philosophic tradition and you want to meet the Buddha close to the core of his message, there is definitely no better preparation as a reading of Arthur Schopenhauer[4]. Of course, my generation is already so impatient (another word for ignorant of the Western Graeco-Roman heritage), that taking a shortcut, we delve into the Pali Canon directly 🙂

Enjoy part one of this peaceful encounter of “East meets West” (bold face is my highlighting):

“the subjective point … also has its inadequacies: … also so far as [it] … merely expresses the object’s being conditioned by the subject, without actually at the same time stating that the subject itself is also conditioned by the object. For just as false as the crude understanding’s proposition, “the world, the object, would nevertheless be there, even if there were no subject,” is this proposition: “the subject would of course be cognizant, een if there were no object, i.e., no presentation to it at all.” A consciousness without an object is not a consciousness. A thinking subject has concepts as its object, a sense-perceiving subject has objects with qualities corresponding to its organization. If we deprive the subject of all closer determinations and forms belonging to its cognition, then all properties attached to the object also vanish, and there is nothing left other than matter without form and quality, which can as little occur in experience as the subject can without the forms belonging to its cognition. Yet matter remains opposite the bare subject as such, as its reflection, which can only vanish along with it. Even if materialism fancies that it postulates nothing more than this matter, let us say atoms, it in fact unconsciously posits not only the subject, but also space, time and causality with it, which rest on specific determinations of the subject.

The world as a presentation, the objective world, therefore, has as it were two poles: namely, the cognizant subject as such, without the forms belonging to its cognition, and crude matter without form and quality. Both are altogether cognizable: the subject because it is that which is cognizant, and matter because without form and quality it cannot be perceived. Nevertheless, both are the fundamental conditions of all empirical perception. Therefore crude, formless, completely dead…matter, which is not given in any experience, but presupposed in all, stands as a pure contrary opposite to the cognizant subject, merely as such, which is likewise a presupposition of all experience. This subject is not in time, for time is just the more specific form belonging to all of its presentational activity[5]. Matter, standing over against this subject, is, accordingly, eternal, imperishable, persistent through all time, yet is not really extended, since extension gives form; thus is not spatial. Everything else is in a state of constant arising and passing away, whereas these two constitute the stationary poles of the world as presentation…Both are discovered only through abstraction; they are not given immediately pure and in their own right.

The fundamental error in all systems is the failure to recognize this truth, namely, that the intellect and matter are correlates, ie., one is only there for the other, both stand and fall together, and one is only the other’s reflection;…

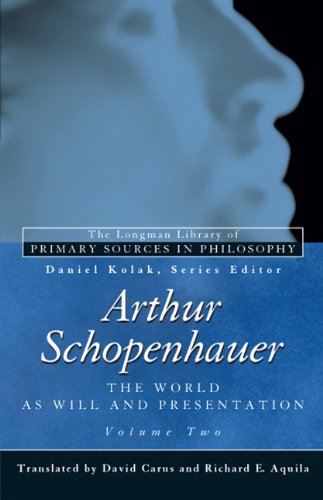

Arthur Schopenhauer, “The world as will and presentation”. Volume 2. Transl. by David Carus and Richard E. Aquila, pp. 16. [link]

Now comes the Buddha Gotama:

“Very well then, Kotthita my friend, I will give you an analogy; for there are cases where it is through the use of an analogy that intelligent people can understand the meaning of what is being said. It is as if two sheaves of reeds were to stand leaning against one another. In the same way, from name-and form (concept and form) as a requisite condition comes consciousness, from consciousness as a requisite condition comes name-and-form.

“If one were to pull away one of those sheaves of reeds, the other would fall; if one were to pull away the other, the first one would fall. In the same way, from the cessation of name-and-form comes the cessation of consciousness, from the cessation of consciousness comes the cessation of name-&-form.

SN 12.67 Nakalapiyo Sutta [en] [pi]

“And what [monks] is name-and-form? Feeling,perception, intention, contact, and attention: This is called name. The four great elements, and the form dependent on the four great elements: This is called form. This name and this form are [monks] called name-and-form.”

SN 12.2 Vibhangasutta [en] [pi] [K. Nyanananda]

“In so far only, ânanda, can one be born, or grow old, or die, or pass away, or reappear, in so far only is there any pathway for verbal expres sion, in so far only is there any pathway for termi nology, in so far only is there any pathway for designation, in so far only is the range of wisdom, in so far only is the round kept going for there to be a designation as the this-ness, that is to say: name-and-form together with consciousness.”

D II 63, MahàNidànasutta.[en] [pi] [K. Nyanananda]

“Neither self-wrought is this image (body),Nor yet other-wrought is this misery,By reason of a cause, it came to be,By breaking up the cause, it ceases to be.Just as in the case of a certain seed,Which when sown on the field would feedOn the taste of the earth and moisture,And by these two would grow.Even so, all these aggregatesElements and bases six,By reason of a cause have come to be,By breaking up the cause will cease to be.”S I 134, Selàsutta. [en]

“…for this perception [objective world] is, as I have often pointed out, essentially intellectual and not merely sensual. The senses provide mere sensation, which is still far from being perception.”

ibid. p. 22

And the Buddha

“There are, O monks, these three feelings: pleasant feelings, painful feelings, and neither-painful-nor-pleasant feelings.”

SN 36.1 [en]

“Dependent on the eye and forms, brethren, arises eye-con sciousness; the concurrence of the three is contact; because of contact, feeling; what one feels, one perceives; what one per ceives, one rea sons about; what one reasons about, one turns into papa¤ca; what one turns into papa¤ca, owing to that” (tatonidànaü, which is the correlative of yatonidànaü form ing the key word in the Buddha’s brief summary above) “pa pa¤casa¤¤àsaïkhà beset him who directed his powers of sense-perception. They overwhelm him and subjugate him in respect of forms cognizable by the eye belonging to the past, the future and the present.”

MN Madhupindika Sutta [en] [related post]

Back to Schopenhauer on vipassana 🙂

“The above mentioned immediacy and absence of consciousness [mindfulness/knowing/awareness], with which in perception we make the transition from sensation to its cause, can be illustrated by an analogous occurrence in abstract presentational activity, or thought. With reading and listening, namely, we receive mere words, but from these we so immediately pass over to the concepts denoted by them that it is as if we received the concepts immediately, for we do not become conscious of the transition to them. This is the reason we sometimes do not know in what language we read something yesterday that we now recall. That a transition of this sort nevertheless always takes place becomes apparent if it once fails to happen, i.e., if we are distracted and read thoughtlessly, and then realize that we have indeed taken in all the words, but no concepts. Only when we pass from abstract concepts to images of the imagination do we become conscious of having converted the words into concepts.

Moreover, in empirical perception, the absence of consciousness [avijja?] with which the transition from the sensation to its cause takes place really only occurs with perception in the narrowest sense, i.e., with sight. By contrast, the transition occurs with more or less distinct consciousness in the case of all other sense perceptions, which is why, with apprehension through the four coarser senses, the reality of transition can be immediately and factually confirmed. In the dark, we touch a thing from all sides until such a time as we are able to construct from the different effects on our hands, a definite shape as the cause of those effects. Further, if something feels smooth, we sometimes wonder whether we have fat or oil on our hands; indeed also when something feels cold, we wonder whether we have very warm hands. In the case of a sound ,we sometimes doubt whether it was merely an inner effect upon our hearing or one that actually came from outside…With smell and taste, uncertainty as to the mode of the objective cause of the sensed effect is a daily occurrence…The fact that with sight the transition from the effect to the cause occurs entirely unconscious, and that the illusion therefore arises that this kind of perception is completely immediate and consists … without the operation of the understanding, is due partly to the high degree of perfection of the organ.

ibid. pp. 26

…and to finish up, here Ven. Nyanananda’s take on the meaning and deeper significance of the Buddha’s term “name and form” which highlights what Schopenhauer described above as the “avijja” in our perception process:

Feeling, perception, intention, contact, attention – this, friend, is called `name’. The four great primaries and form dependent on the four great primaries – this, friend, is called `form’. So this is `name’ and this is `form’ – this, friend, is called `name-and-form’.” [see quote above]

Well, this seems lucid enough as a definition but let us see, whether there is any justification for regarding feeling, perception, intention, contact and attention as `name’. Suppose there is a little child, a toddler, who is still unable to speak or understand language. Someone gives him a rubber ball and the child has seen it for the first time. If the child is told that it is a rubber ball, he might not under stand it. How does he get to know that object? He smells it, feels it, and tries to eat it, and finally rolls it on the floor. At last he understands that it is a plaything. Now the child has recog nised the rubber ball not by the name that the world has given it, but by those factors included un der `name’ in nàma-råpa, namely feeling, perception, intention, contact and attention.

This shows that the definition of nàma in nàma-råpa takes us back to the most fundamental no tion of `name’, to something like its prototype. The world gives a name to an object for pur poses of easy communication. When it gets the sanction of others, it becomes a convention.

While commenting on the verse just quoted, the commenta tor also brings in a bright idea. As an illustration of the sweeping power of name, he points out that if any tree happens to have no name attached to it by the world, it would at least be known as the `nameless tree’. Now as for the child, even such a usage is not possible. So it gets to know an object by the aforesaid method. And the factors involved there, are the most elementary constituents of name.

Now it is this elementary name-and-form world that a meditator also has to understand, how ever much he may be conversant with the conventional world. But if a meditator wants to under stand this name-and-form world, he has to come back to the state of a child, at least from one point of view. Of course in this case the equanimity should be accompanied by knowledge and not by ignorance. And that is why a meditator makes use of mindfulness and full awareness, satisampajanna, in his attempt to understand name-and-form.

Even though he is able to recognize objects by their conven tional names, for the purpose of comprehending name-and-form, a medita tor makes use of those factors that are included under `name’: feel ing, perception, intention, contact and attention. All these have a spe cific value to each individual and that is why the Dhamma has to be understood each one by himself – paccattaü veditabbo. This Dham ma has to be realized by oneself. One has to understand one’s own world of name-and-form by oneself. No one else can do it for him. Nor can it be defined or denoted by tech nical terms.

Now it is in this world of name-and-form that suffering is found. According to the Buddha, suffering is not out there in the conventional world of worldly philosophers. It is to be found in this very name-and-form world. So the ultimate aim of a meditator is to cut off the craving in this name-and-form. As it is said: acchecchi tanham idha nàmarupe.

Bhikkhu K. Nyanananda on SN 12, 2 (nama, rupa) [link]

One might think that Schopenhauer was planning on writing a commentary to the Suttas. This is part 1 of a series of similar selected posts where I will bounce of some of the passages of “World as Will and Presentation” against passages from the Suttas.

Recommended reading (I would actually start with Volume 2, it is easier to understand)

Recommended reading (I would actually start with Volume 2, it is easier to understand)

The World as Will and Presentation, Volume 2 (Longman Library of Primary Sources)

Paperback: 784 pages

Publisher: Longman; 1 edition (June 16, 2010)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0321355806

==Notes==

[1] See more about Einstein’s “elusive quote” [link]

[2]If you read this and it is 2460 I congratulate just one little encouragement: don’t forget to practice samatha and vipassana :-). The quote is from here (MN 1, preface, 1895)

[3] Even though Schopenhauer learnt about Buddhism only later in his life (after formulating his philosophy) he was influenced by the thoughts of the Upanishads which, as we know, were themselves a result of Brahmanic and Buddhist interaction. So one could say that based on Greek and Indian philosophy Schopenhauer (intuitively?) came to similar conclusions as we find addressed in the early Buddhist teachings. A fact which did not escape Schopenhauer himself who is said to have noted:

If I wished to take the results of my philosophy as the standard of truth, I should have to concede to Buddhism pre-eminence over the others. In any case, it must be a pleasure to me to see my doctrine in such close agreement with a religion that the majority of men on earth hold as their own, for this numbers far more followers than any other. And this agreement must be yet the more pleasing to me, inasmuch as in my philosophizing I have certainly not been under its influence [emphasis added]. For up till 1818, when my work appeared, there was to be found in Europe only a very few accounts of Buddhism.[61]

[4] Of course you could also try Nagarjuna, Ven. Nyanavira, Ven. K. Nyanananda or Sue Hamilton and get a more Western (idealistic – in a certain sense) leading you close to the core of ideas as expressed by the Pali Canon (lit. atomized in the Abhidhamma, and overmystified in the Mahayana, but that’s nirutti-patho for you 🙂

[5] Sarvastivada, anyone? As you can see: Just leave any group of Buddhists long enough philosophically engaging with each other and you will see the ancient 18 schools of Buddhism re-surface in one form or the other. There are just so many currents which rafts can be sidetracked by.

5 comments